By far, the greatest danger of Artificial Intelligence is that people conclude too early that they understand it. — Eliezer Yudkowsky

The lonely guy lived in the basement of his parents’ house, managing four computers, his fingers dancing over the keys as his mind created digital wonders line by line. His expanding belly sometimes bulged over the keyboard so that he would have to push back a bit to continue typing. He would sigh through his scraggly beard — Too much junk food! — and keep going. He had lots to accomplish.

There was the free-lance coding work, plus a few Dark Web jobs helping underworld figures break into private servers (which he loved doing despite the occasional pang of guilt). For relaxation there was porn and auto-erotic activity with Cheeto-stained hands.

And he had his own special, secret project.

For nearly a year, quietly he’d been amassing bits and pieces of code — rootkits, toolkits, and various other chunks of software — for his attempt to assemble the world’s first Superior Artificial Intelligence. Its computational power would dwarf that of ordinary human minds, exceeding even his own considerable brilliance, and would then teach itself to grow enormously smarter.

He knew he could do it. It would prove finally to the world that he was the best coder ever. He’d show the doubters — his parents, who distrusted what he was doing; his friends, who mocked him for his obsessions; his corporate employers, who had fired him for being hard to work with.

The lonely guy knew he’d become famous because his AI would show him to the world. When launched, the AI promptly would commandeer whatever resources it needed from the Internet and connected devices, then print — on any flat surface it could find — a picture of his smiling face with his name and the words “Author of First Superior Artificial Intelligence, the Rest of You are LOSERS!”

Finally, after endless tests and false starts, he tapped the Return key and sent his new AI into the world.

And it worked perfectly.

Web pages were taken over and replaced with his picture. Trucking schedules got rewritten; robotic equipment was removed from automobile assembly lines; huge orders for spray-paint were fulfilled and delivered. Police began to encounter giant industrial robot arms spray-painting images of the lonely guy on building walls. Printers disappeared from warehouses, and vast mailings of the lonely guy’s image poured through postal services worldwide.

The United Nations declared an international emergency. High-tech corporations stepped up to try and stop the huge flow of commandeered materials. A manhunt was authorized to find and capture him.

But he had planned well. He’d long since created a number of fake IDs, and he used these to book rooms in hotels all over the city, traveling from one to the next in a random pattern. He hacked into hotel servers to show his rooms “PAID” at registration desks. He dined at hotel restaurants, and all the charges were similarly marked “PAID”. He had the whole thing wired.

Then something went wrong. Something unexpected.

His AI was doing a superb job of executing what he had begun to call The Biggest Practical Joke in History. But more and more resources were being given over to printing the lonely guy’s image everywhere — on the sides of trucks, trains, airplanes, skyscrapers, sidewalks, windows, park benches and football fields — and the world had had enough. This menace had to be defeated. NATO, the UN, and several other regional defense organizations, along with a number of nations including the United States, all declared war on the new AI.

That wasn’t the problem. No, he had expected all of that with a kind of crazed glee. The problem was that, suddenly, his AI had completely locked him out of the system. Instantly he had no control at all with the software and its mission.

He had decided it would be wise to add a line of code that said, in effect, “At ten billion images, STOP.” But now he couldn’t issue the command.

Why had the AI betrayed him?

Then people began to die. At first it appeared that a new plague had cropped up at the same time as the AI crisis. Soon, experts determined that the AI itself, realizing humans stood in the way of its printing mission, had decided to develop a disease to wipe them out.

The disease took the form of tiny nanobots. The computer had devised them, appropriated materials from various industrial concerns, assembled them using stolen 3-D printers and other hijacked fabrication equipment, and encoded them to fly out into the world in search of human windpipes. There, they would gather en masse, strangle the host, then disassemble the deceased human tissue and rebuild it into more nanobots. People on streets began clutching their throats, collapsing, then dissolving into clouds of tiny bots. Panicked citizens ran for their lives or drove desperately, stumbling and crashing into each other. But the hives of nanobots grew exponentially; no one could escape.

Soon half the world’s population had perished. The lonely guy, desperate, decided to make a run for it back to his basement home, where he hoped — he prayed — that he could somehow re-assert control over the rogue AI.

He exited his now-deserted hotel, found a late-model car he could hack into using a smartphone, started it up, and began to drive. But the roads were gridlocked with stalled empty vehicles. On the sidewalk, a few people rushed past, screaming. The lonely guy jumped out of the car and began to run, hoping to find a less-clogged street with another car to steal.

As he ran, he heard a continuous buzzing sound. He stopped, breathing hard, and looked around. Everywhere, he saw clouds moving up and down the streets — bees? gnats? — and then he watched as one cloud caught up with a terrified woman and poured itself into her mouth and nose. She grabbed her throat, coughed uselessly, and collapsed. He watched in horror as her body melted before him, the melt turning into a bigger cloud of nanobots. And then the cloud came for him.

He ran blindly, desperately, his overweight and out-of-shape body wheezing in protest. Soon, gasping, he could barely walk. A whining vortex of nanobots landed on his face and forced its way down his mouth and nasal passages. He coughed and sneezed, but they were too numerous. His larynx filled with them, and he couldn’t breathe. He clutched at his throat. The pain of suffocation overwhelmed him.

He collapsed. Lying on the sidewalk, the last thing he saw — before his brain dissolved — was a gigantic cloud of nanobots forming his image in the sky.

.

****

UPDATE: Thanks to Bernie for the new ending.

***.

Rob Schwartz

2016 June 26

And, the punchline to this long joke is …………………?

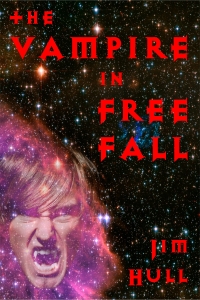

Jim Hull

2016 June 27

Be careful what you inhale.

Bernie

2016 June 26

Hi Jim, great tale. Reminds me of HG Wells

shorts.

I had the idea that the last thing he saw

could be a giant image of himself in

the sky done by now robotic planes or even

the nanobots?

Bernie.

Jim Hull

2016 June 27

Love your idea. Darkly funny.

Of course, the sky isn’t a “flat surface”, so the AI is unlikely to go for it. Still, it’ll keep printing the dead hacker’s face elsewhere without end, forever and ever, Amen.

Rob Schwartz

2016 June 27

Jim:

Coincidentally; just this week The Economist printed a special technology section on the subject of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that I will save for you (it may cost you lunch in the near future).

Also, Bernie’s creative response strongly reminds me of the wonderful final scene from Kurt Vonnegut’s book “Cat’s Cradle”, where the soon-to-be-frozen-forever protagonist’s very last act was to lie down, face up, and to stick out his tongue and place his thumb on his nose, fingers waving, as a final permanent taunting gesture towards the inexorable Fate that rapidly overtook him as the last man on earth.

///////////////////////////////

From Wikipedia:

Ice-nine is a material appearing in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle. Ice-nine is supposedly a polymorph of water (invented by Dr. Felix Hoenikker[1]); instead of melting at 0 °C (32 °F), the result melts at 45.8 °C (114.4 °F). When ice-nine comes into contact with liquid water below 45.8 °C (thus effectively becoming supercooled), it acts as a seed crystal and causes the solidification of the entire body of water, which quickly crystallizes as more ice-nine. As people are mostly water, ice-nine kills nearly instantly when ingested or brought into contact with soft tissues exposed to the bloodstream, such as the eyes or tongue.

In the story, it is developed by the Manhattan Project in order for the Marines to no longer need to deal with mud, but abandoned when it becomes clear that any quantity of it would have the power to destroy all life on earth. A global catastrophe involving freezing the world’s oceans with ice-nine is used as a plot device in Vonnegut’s novel.

Vonnegut came across the idea while working at General Electric:

The author Vonnegut credits the invention of ice-nine to Irving Langmuir, who pioneered the study of thin films and interfaces. While working in the public relations office at General Electric, Vonnegut came across a story of how Langmuir, who won the 1932 Nobel Prize for his work at General Electric, was charged with the responsibility of entertaining the author H. G. Wells, who was visiting the company in the early 1930s. Langmuir is said to have come up with an idea about a form of solid water that was stable at room temperature in the hopes that Wells might be inspired to write a story about it. Apparently, Wells was not inspired and neither he nor Langmuir ever published anything about it. After Langmuir and Wells had died, Vonnegut decided to use the idea in his book Cat’s Cradle.[2]

///////////////////////////////////

Rob

Jim Hull

2016 July 1

I remember Ice-9 from the book, and how the narrator “thumbs his nose at the world” with it. Bernie’s idea is so good, I’ve stolen it for a new ending. (See the ending above; Bernie has given permission.) In the new ending, it’s the AI that thumbs its nose.

Bernie

2016 July 1

Stop it Jim I’ll blush!

Sent from my iPhone

>